Swords, Songs, Stitches and a Riddle: the Battle of Hastings – 2025

14 Oct 2025

An overcast day on an October weekend… a hillside in Sussex… mighty forces drawn up against each other… the English at the top of the hill behind their shield wall… the Normans at the bottom of the hill with their archers and knights… it has to be the Battle of Hastings.

This year’s reenactment took place on the 11th and 12th October and was a spectacular of music, crafts, food, displays, entertainers, and of course the reenactors lining up on the English and Norman sides for armed combat at the end of the day.

I toured the English Heritage site, which now contains the ruins of the abbey William the Conqueror had built, as well as the presumed location of the battle, with copies of Thegn of Berewic in my rucksack and in the company of my wife Linda. We were not disappointed…

The sounds of time

The musical duo of Vicki Swan & Jonny Dyer @swandyermusic behind the ‘Sounds of Time’ live shows took us to the music of the era before the Norman Conquest, and the era after. The point being, as they told us, that not a lot of Anglo-Saxon music survived into the conquest era partly because it was so disruptive. Instruments like the drum, harp, cytere, willow pipe, recorder and bagpipe were on show and taken expertly through their paces with witty commentaries, followed by a short dance for those prepared to have a go.

The Sounds of Time

Music from before...

Music from before...

... music from after

... music from after

One of Jonny’s songs featured the riddle number 5 from the Exeter Book, a large codex of Old English poetry believed to have been written in the 10th century, and which includes almost a hundred riddles. Many of these are wonderfully risqué double entendres, though not riddle 5 which in Anglo-Saxon looks like this:

Ic eom anhaga iserne wund,

bille gebennad, beadoweorca sæd,

ecgum werig. Oft ic wig seo,

frecne feohtan. Frofre ne wene,

5 þæt me geoc cyme guðgewinnes,

ær ic mid ældum eal forwurðe,

ac mec hnossiað homera lafe,

heardecg heoroscearp, hondweorc smiþa,

bitað in burgum; ic abidan sceal

10 laþran gemotes. Næfre læcecynn

on folcstede findan meahte,

þara þe mid wyrtum wunde gehælde,

ac me ecga dolg eacen weorðað

þurh deaðslege dagum ond nihtum.

English translation:

I am a lone-dweller, wounded by iron,

savaged by a sword, worn out by war-deeds,

battered by blades. Often I see battle,

fraught fighting. I do not expect succour,

5 that relief from war might come to me,

before I perish utterly among men,

but the leavings of hammers lash me,

hard-edged and sword-sharp, handiwork of smiths,

they bite me in strongholds; I must wait for

10 the more hateful encounter. Never am I able

to find medic-kin in the dwelling-place,

those who might heal my wound with herbs,

but the scars of swords become wider on me

through a death-blow by day and by night.

Source: https://theriddleages.com/riddles/tag/riddle%205/

The answer to the riddle is hidden later in the blog …

Food and fibre

Many of the reenactors were there not just to brandish weaponry but to recreate as faithfully as possible daily life in the 11th century in the form of preparing and cooking food, and creating fibre out of natural materials and weaving, spinning and dying it.

Anglo-Saxons were ingenious in harvesting wild animals and plants from the land around them and making them fit to eat alongside the produce from their domestic crops and livestock. So weed seeds and acorns, hare and deer had their place alongside oats and barley, pigs and chickens.

Even so, the threat of hunger was constant, and the Anglo-Saxon chronicles record frequent years of famine. Without supermarkets and freezers, survival depended on being able to grow and store – if necessary preserving as well – enough food to last into the hungry months. These were not as you might imagine late into winter, but just before food production and harvesting resumed in summer. Hungry times are never far away in Thegn of Berewic, and Eadric’s arrival in the village coincides with one.

There was much demonstration and discussion among the Battle reenactors of how foods might be flavoured with herbs and spices (perhaps to hide bad flavours too), and sweetened. Without sugar, honey was the main natural form of sweetener as well as an important ingredient in the drink mead. The photograph below shows ‘Anglo-Saxon’ and ‘Norman’ cakes for sale at the event – the ‘local’ cake sweetened with honey, and the ‘foreign’ date cake containing spices. I have to say, this one was very nice…

Cooking was over a wood fire and there was an ingenious range of cooking devices on show, often incorporating hooks, racks and spits, some of these with a tasty if well-cooked rabbit on them (anticipating the later introduction of the species by the Normans). Now, the seax was a versatile tool – it could be carried as a cutting knife as in the photograph, or used as a weapon like a small sword, especially as a larger version carried by a high status person. In The Book and the Knife the seax is used as a weapon quite a lot, beginning from when Sighere kills the messenger from Normandy who brings him unwelcome news. Note in the photograph the reenactor’s neat blue bag with the wooden clasps – I think Ralf might have had a bag like this for his fire-making equipment.

We think of the Anglo-Saxon age as rather drab without access to the range of synthetic colours we have now. Far from it – yellows, oranges, browns, blues, reds, and purple for the very wealthy, were available from natural sources, even if sometimes exotic ones such as cochineal from insects. The photograph below shows dyed yarns and some of the sources of the dyes, including weld [yellow], woad [blue], oak galls [black] and madder [red]. In Thegn of Berewic, Æadgytha’s wedding gown is made of fine linen, and dyed pale blue.

Get your Saxon and Norman cakes here

Get your Saxon and Norman cakes here

Top of the range cooking range C11

Top of the range cooking range C11

The seax, a versatile tool (or weapon)

The seax, a versatile tool (or weapon)

Dyes and dyeing on display

Dyes and dyeing on display

A stitch in time

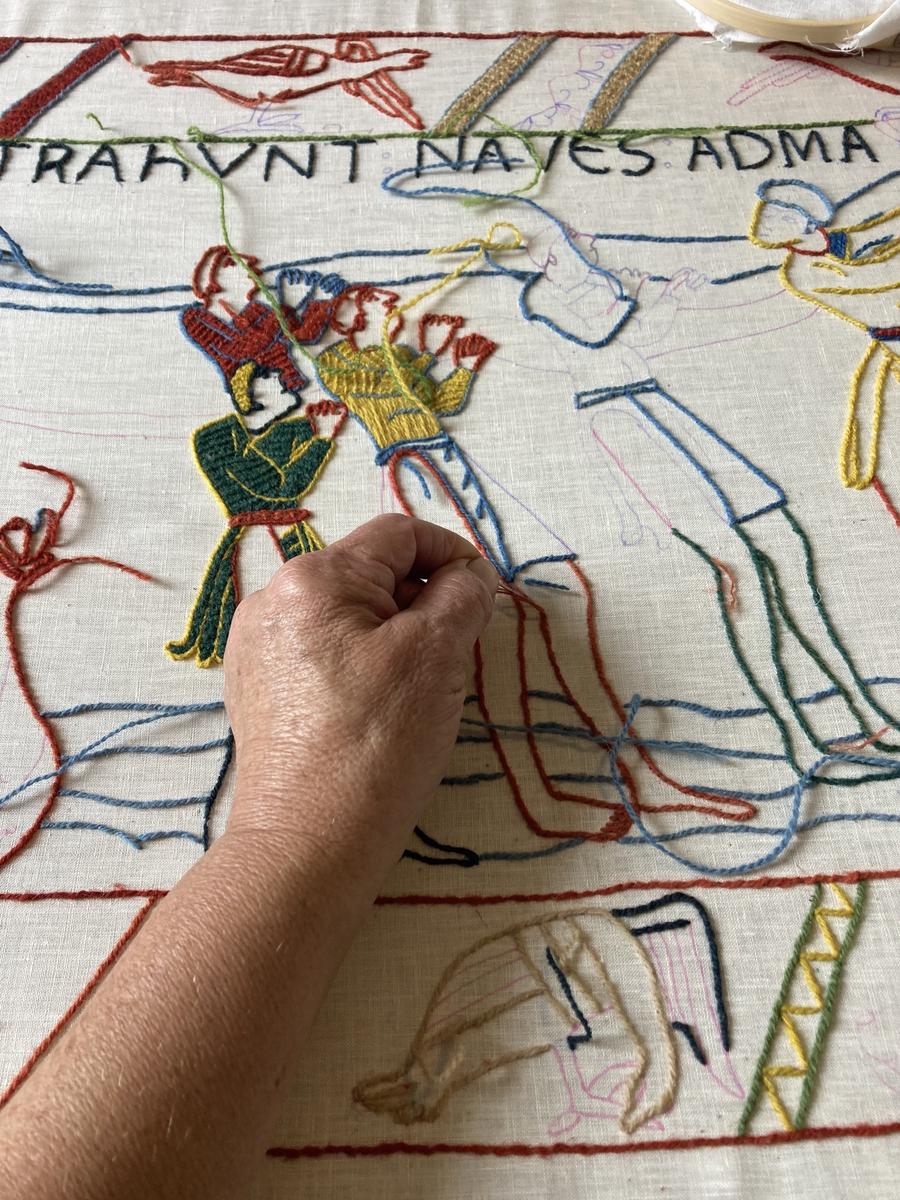

One of the most interesting displays on the day was a needlework demonstration by the La Mora Project. The work of La Mora (named after Duke William’s flagship) includes recreating panels from the Bayeux tapestry. Visitors are invited to ‘help stitch history’ by adding a stitch to panels depicting the building and launching of the ships for William’s invasion fleet – after a practice run on a round sampler. Linda set to work with blue thread on the leg of a man in a team dragging a ship to the sea (you can see part of the Latin text "Hic trahunt naves ad mare" = "Here they drag the ships to the sea").

The Bayeux tapestry was indeed not a tapestry but an embroidery. It may well have been commissioned by William’s half-brother Odo who fought with him in the battle and was rewarded with extensive lands in Kent. The needleworkers could then have been women local to Canterbury, working to a design by the abbot of St Augustine’s abbey in the town. There are other theories as to the origin of the ‘tapestry’, eg it was commissioned by:

· Matilda, William’s queen who gifted him his ship the Mora, or by

· Edith, widow of King Edward ‘the Confessor’ and brother of Harold Godwinson

If it was commissioned by Edith, it may have been executed at Wilton abbey, her place of refuge after the conquest. Edith and Wilton feature a lot in later parts of The Book and the Knife, but in my novels Edith has another activity that is meant to undermine the rule of the Normans (no spoilers here though).

A panel in progress

A panel in progress

Easy does it...

Easy does it...

... there we go !

The armed man

Not surprisingly armour and weapons were much in evidence at the reenactment. You could heft a chain mail shirt (heavy, though its weight is evenly distributed), and wield a spear or a sword. A spear was generally the weapon of a foot soldier in the fyrd, the English militia, being cheap as it needed little metal to make the tip. A sword of course needs not only much metal, but iron or steel of good quality finely wrought so it does not shatter when used, so it was the weapon of a higher class and wealthier fighter, such as a huscarl, one of the king’s bodyguard.

According to the Anglo-Saxon living history organisation Regia Anglorum, “in addition to his sword, a huscarl would also have been expected to have a horse to carry him to the battle (although he would dismount and fight on foot), a mail-shirt, helmet, shield, spear, and, of course, the 'massive and bloodthirsty two handed axe'”. In Part Three of The Book and the Knife, one of my characters who has become one of King Harold’s huscarls fights with him in the Battle of Hastings, wielding an axe. Harold has his own reason to put this man in the shield wall, where he may live or die…

A few axes among a detatchment of fighters parading at the English camp

A mix of shield types in a line up for inspection in the English camp

Mail, helmets and weapons in the Norman camp

A helmet with a noseguard provided protection to the head, but the eyes and mouth were still vulnerable to a thrust from a spear or sword, from a crossbow shaft or the flight of an arrow (take note, Harold). To protect the body in close combat, the fighter needed a shield. Worn on the non-sword arm, this had a handgrip on the back, with the fist placed behind the centre boss if there was one.

The shield could be used to take arrow shots and parry blows as well as push an opponent off-balance or bludgeon him with the spiked metal boss in the middle, but it needed to be strong and ideally light. The shield maker in my photographs takes issue with the idea of shields being made of lime, putting forward alder and pine as alternatives. He certainly makes a high quality product – one which as he said its owner might well leave at home and take a more workaday model into the fight.

The kite-shaped shield associated with Norman knights but also carried by Norman foot-soldiers, protected the whole body. It could be slung round the neck on a strap or carried on the left forearm when riding, leaving the left hand free for the reins. It also had handgrips to hold it when fighting on foot.

The English, who normally fought on foot, are often shown carrying round shields. In fact some, especially the huscarls, also carried kite-shaped shields, while others used stronger and heavier round wooden shields. Both types could be interlocked together to form the defensive 'shield wall'. Note the raven image on one of the shields in my photographs. A white raven is a powerful emblem in Norse mythology, associated with prophecy and magic and with the power to see into the future and predict the outcome of battles. In Part Four of The Book and the Knife one of my characters fights as the White Raven, with such an emblem on their shield.

On the arm of an experienced warrior, a shield must have felt like an extension of the body. Of course the poor shield, wounded by iron, savaged by a sword, never able to find medic-kin in the dwelling-place as the warrior would, has to endure its fate …

Kite-shaped shields on show in the Norman camp

Kite-shaped shields on show in the Norman camp

Starting with this, the shield maker makes...

... this! A work of art

The grip and handhold

A raven emblem shield

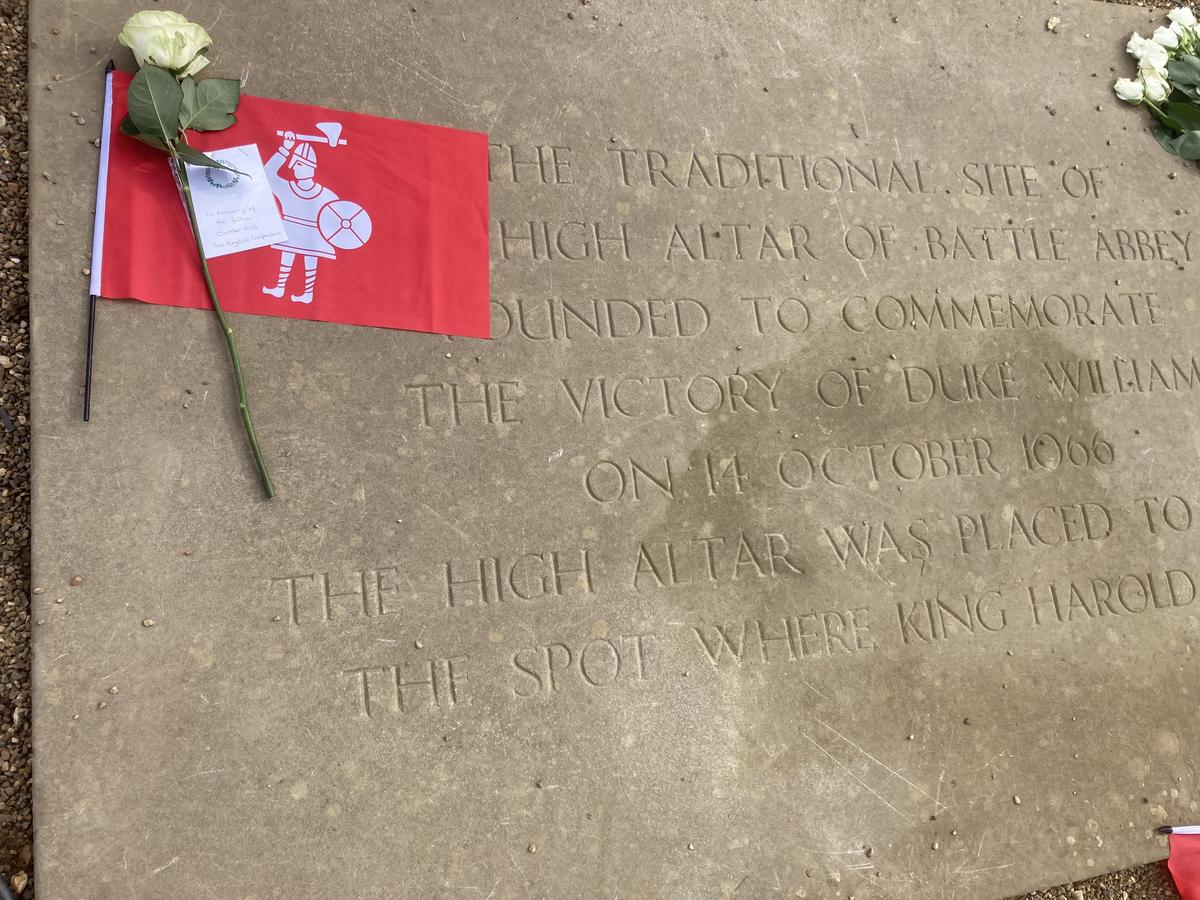

And so to the battle… but that’s for another blog. We know the outcome, and it was no different on this reenactment weekend. One of the most poignant sights of the day was at the Harold Stone, the spot where the king is said to have died, and where William placed the altar of the abbey he later had built. White roses had been laid, and with a small ‘Armed Man’ banner like King Harold’s, a note read; “in memory of the fallen”. May they have eternal peace.

At the Harold Stone